While the Soviet Union was governed by a single communist party for sixty-nine years, it was the Stalinist era spanning 1924 to 1953 that were the most memorably brutal. Nobody escaped the scrutiny of this iron-clad regime and in 1932, Stalin dissolved all literary groups and put a new Union of Soviet Writers in place. From then on, Soviet Literature was to be inspired only by politics which meant total submission for the arts as well.

Many Russian writers took to writing historical novels and plays to remain under the radar. But as is the way in a time of political turmoil, other writers went underground, taking great risks to bring the truth to the world beyond Soviet Russian borders. Books were written secretly and smuggled out to be published abroad. Some books written during those years only came to light after Stalin’s death.

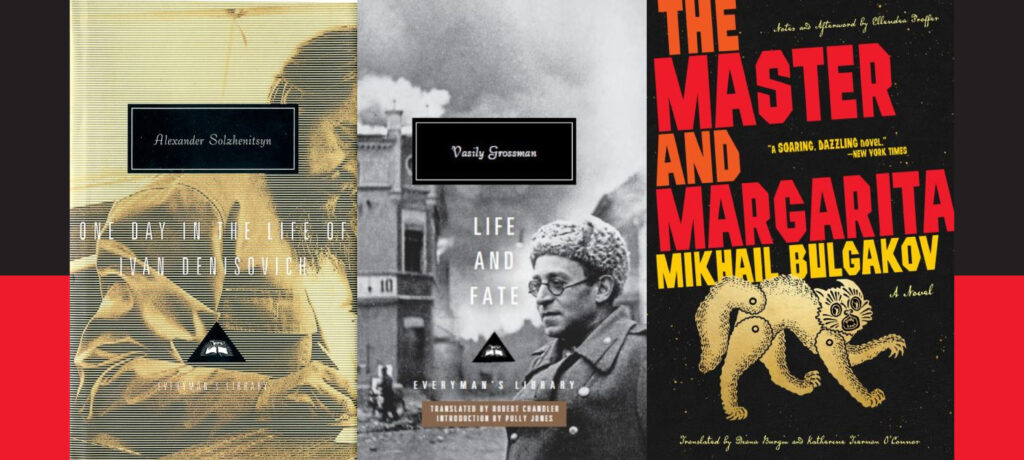

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was for me, the greatest amongst Russian writers. I remember my absolute awe when I read One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich for the first time. The stark immediacy of the writing, the minute detail of the intolerable life of a prisoner in the Gulag drew raw emotion from me. It also made me greedy to read more of Solzhenitsyn’s work and there was plenty more to read.

Solzhenitsyn, himself a victim of the Soviet regime, was imprisoned in the Gulag for eight years having criticised Stalin in a private letter to a friend. Released only after’s Stalin’s death, he immediately began work on Ivan Denisovich for which he was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. With the support of the more moderate Khrushchev, the novel was first printed in the Soviet journal Novy Mir in 1962. There followed other great works: Cancer Ward, The First Circle, The Gulag Archipelago which was a public challenge to the Soviet system. These however were published abroad for by then, Khrushchev was out and the harsh regime resumed under Brezhenev.

Another great book as part of Soviet literature, The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov, often described as one of the greatest novels of the 20th century, was written between 1928 and 1940. Bulgakov destroyed an earlier draft of his novel which satirised the Soviet state, believing he could not have a career as a writer in his own country. But he later went on to write several more drafts and died in Paris in 1940 shortly after finishing it. Although a censored version was initially published in Russia, a full manuscript was smuggled to Paris where YMCA Press, who also published the novels of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, published The Master and Margarita in 1967.

During World War Two, the author Vasily Grossman worked as a journalist for a Red Army newspaper giving first-hand accounts of battles at Moscow, Stalingrad and Berlin. He also gave eye-witness accounts of the extermination camp at Treblinka, some of which were later presented at the Nuremberg Trials. The first part of his novel, Life and Fate, was written during his loyalty to the regime, but gradually his loyalties changed and the second part was very critical of Stalinism. Both the novels, Life and Fate and Everything Flows, were censored by Khrushchev for being anti-Soviet. The manuscripts were confiscated by the KGB in a raid on his home. At the time of Grossman’s death in 1964, neither of these novels had been published, although later, copies were smuggled out of Russia by sympathisers. Life and Fate was finally published in 1980. His novel The People Immortal portrays Russia during the German invasion, a heroic story of resistance from Grossman’s personal experience.

The suffering and brutality of the Stalinist years is perhaps best described by the great poet, Anna Akhmatova, who remained in Russia despite great personal danger. Her first husband was arrested and executed. Her son, a celebrated historian, was also arrested and sent to the Gulag. Akhamatova wrote Requiem over three decades to describe not only her own grief but that of the hordes of distraught women who queued each day in all weathers in the vague hope of hearing news of their husbands, sons and fathers. Requiem was first published in 1963 in Munich but without the poet’s consent.

Some of these great works are perhaps less well valued or appreciated today, but they are without doubt an important part of a large body of Soviet literature that carried on the tradition of Tolstoy, Chekhov and Dostoyevsky. They define an unspeakable time in the history of a country which has yet to find peace with itself.

Recent Comments