When I was pregnant with my first child, a woman I’d barely spoken to came over to me in the office toilets and touched my belly. It felt like such a transgression to me – but she didn’t even notice me flinch.

Later that week, at a work dinner, a colleague held up a palm to stop a waiter pouring wine into my glass. ‘Just four glasses, please.’

We all know what is expected of us as mothers-to-be. Shy Princess Diana smiles. Deference to the gods of medical science, with their sweeping diktats about runny eggs and bloody steaks. And, though no one will say it explicitly, we’re supposed to stay looking hot. If at all possible.

For a while, I couldn’t work out why I felt physically sick whenever someone told me, looking approvingly at my expanding middle, that I “looked great”. I later realised it was the knowledge that my changing body was suddenly up for examination and discussion. Worse still, that people thought this was what I wanted to hear. To be reassured I was ‘winning at pregnancy’ by not getting too fat.

Late pregnancy was the most psychologically strange time in my life. A waiting room between a life that was already gone, and a new one that was completely unknowable. My old life had been so curtailed I didn’t recognise it – I couldn’t drink, I couldn’t do ‘proper’ yoga, I couldn’t fly. Even a hot bath at the end of another wearying day was verboten. I had pregnant friends who seemed not to mind these rules, even to find them reassuring. I was enraged by them. I stubbornly clung to my occasional glass of red wine, my slivers of charcuterie. I endured the raised eyebrows.

But as time went on, I started to barely recognise myself. It wasn’t just my body that felt unfamiliar – dominated by my enormous imposter, so large now its elbows and feet rose alien-like under the surface of my skin. My mind felt sapped of energy, my thoughts vague and fuzzy. Having barely ironed an item in my life, I now spent hours pointlessly ironing tiny, white baby grows, while gormlessly watching mothercare videos on YouTube. Even my tastebuds had changed. Who was this huge, laundry-obsessed woman, I wondered sometimes, who ate only milkshakes and macaroni cheese?

It’s in this psychological no mans’ land that my character, Helen, finds herself. Her doomed friendship with the unpredictable Rachel – who she meets at her antenatal class – is a product of the specific strangeness and loneliness of this time. A time when the forced intimacy of the antenatal group can contrast with the horrid, drifting feeling of other relationships, the unexpected wrinkles pregnancy can create with other women. Because suddenly, for other people, you are no longer just yourself but a very specific symbol. Perhaps of the bump they don’t want – or not yet – and that they are secretly disappointed you’re going to have, because they feel, already, how it will change everything. Worse, of the bump they are longing for, or have lost. You don’t mean to be any of these things. You just are. You have lost control over what you represent.

And loss of control is unfamiliar to us, as 21st century women. Unquestioning obedience might have come naturally to our mothers and grandmothers, but our brains can barely compute it. We have become used to controlling, to the millimetre, our diets, our appearance, our relationships; to carefully curating the images we project of ourselves. Pregnancy brings a total loss of that control. We can’t control how it ends, either – however many birth plans we write, however many books we read. Our conscious minds have no dominion. We are in the hands of our bodies, of other people, and of fate. What could be more terrifying?

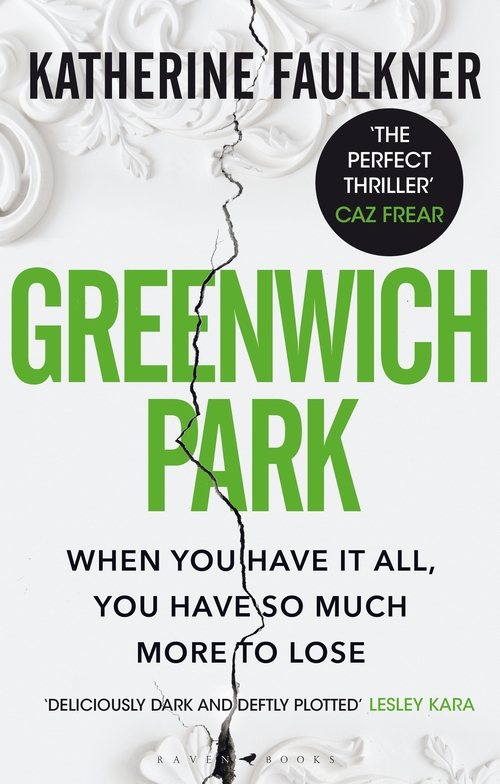

Katherine Faulkner studied History at Cambridge then completed a postgraduate diploma in Newspaper Journalism. After working as an investigative reporter, during which time she won the Cudlipp Award for public interest journalism, and as an editor, she went on to become joint Head of News at The Times. Katherine is now writing full time.

She wrote her debut novel while on maternity leave, juggling a newborn with completing the Faber Academy novel-writing course. She lives in Hackney, where she grew up, with her husband and two daughters.

Recent Comments