When I was a kid, there was a henna plant outside my grandmother’s apartment. It was one of my favourite things in the world, because every once in a while, me and my cousins would run out to the henna plant to pick its leaves. We would come back to my grandmother’s apartment and crush up the henna leaf to make henna paste. Later, we would use toothpicks to draw a design onto the palms of our hands. And we would clump up the henna onto our fingernails to dye them red.

In Bangladeshi culture, henna is both celebratory and an every day part of people’s lives.

This is how I grew up, surrounded by henna. It was a pretty natural part of my life. In Bangladeshi culture, henna is both celebratory and an every day part of people’s lives. My cousins and I would use it to in the place of nail polish to paint our nails red (and it works better and lasts longer, and has a beautiful red/orange colour), and I would see my Uncles use it to dye their beards, or my Mom and Aunts use it to keep their hair healthy. Then there are the ways that Westerners usually see henna being used and that is for decorative purposes. Fancy wedding henna designs from the tip of our fingers all the way to our elbows. Intricate flowers and leaves and vines.

I didn’t really think much about henna before I moved to Ireland, and realised that the way it existed in my life wasn’t the way it existed in everybody else’s life. In fact, after coming to Ireland I slowly began to grow an aversion to henna, something that had always been a huge part of my culture and life. It was because the way people viewed henna here made me realise it was different and that I was different for wearing it. Me and my other Muslim friends were told that we weren’t allowed to come into school with henna on our hands. It was forbidden.

The problem is that most natural henna is a very strong dye. This means that if I applied henna on my hands to celebrate Eid over a weekend, the henna wouldn’t rub off from my hands for weeks or months. It meant that even when I went back to Bangladesh for the weddings of Uncles or Aunts or cousins, I watched my Bangladeshi family put henna on their hands and hesitated to let them apply any henna to me. What if I went back to school months later with henna still on my hands? Would I get into trouble?

Slowly, but surely, the way I viewed henna as a kid picking leaves off of my grandmother’s henna plant changed. Yet, despite the fact that I was made to feel bad for my relationship with henna, I noticed the way other people—for whom henna was not a part of their culture—viewed it. For my classmates it was something odd, but pretty. Something that they desired; not because it was a part of their culture, but simply for the aesthetic beauty of it. So, henna was something “trendy” or “cool,” but there were so many other parts of my culture that absolutely was not.

As a teen, it was immensely difficult to figure out how to feel about my own culture when there were so many complicated things going on concerning it. It felt like navigating my own feelings, how I straddled these two cultures—Bangladeshi and Irish—didn’t really belong to me. I had to entertain outsider opinions, thoughts; sometimes I was expected to deride things I grew up with simply because it might help me “fit in.”

Meeting other people of colour from various cultures, with their own complicated thoughts and feelings helped

As I grew up though, thankfully, I got to return to my culture having figured out many of these complicated thoughts and feelings. Meeting other people of colour from various cultures, with their own complicated thoughts and feelings helped with that. So did being able to study all of the amazing people writing about culture, race, and more. Finally, as an adult, I had language that I wished I had when I was a kid. I could finally voice all of the conflicting things that had happened to me as a kid…but who was I going to tell them to?

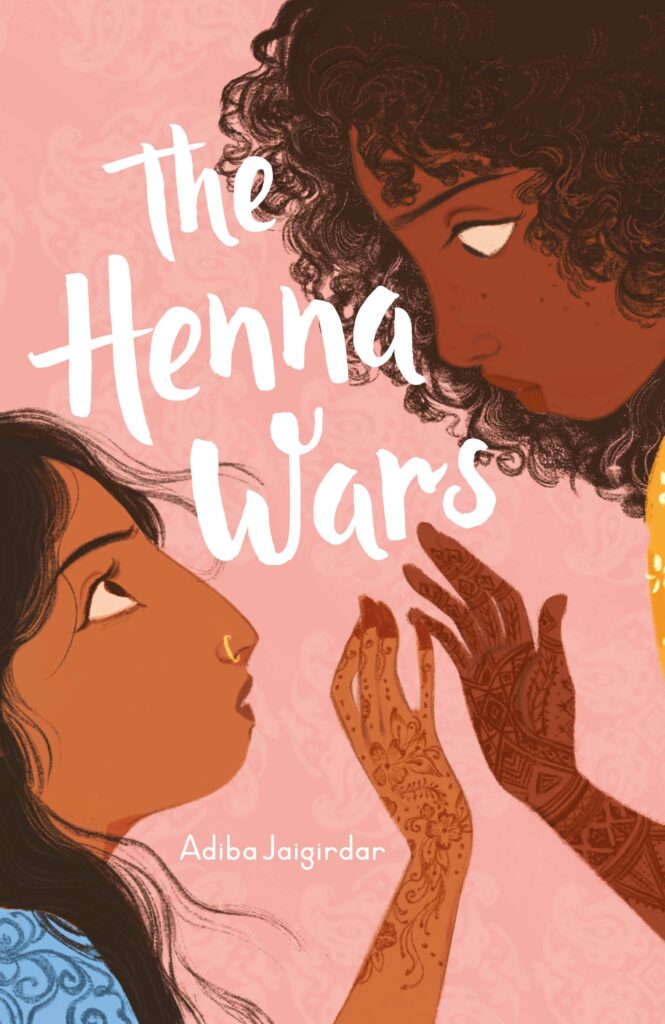

When I sat down to write The Henna Wars, these are all of the things I was thinking of. My culture, something that is a complicated, but important part of me. Both Bangladeshi and Irish, both the girl picking henna leaves off her grandmother’s plants and the one who feared putting henna on her hands in case she got in trouble at school. And along with that, all of these experiences I had as a teenager that I couldn’t figure for years, that I couldn’t voice out loud. With The Henna Wars, I knew that I could give a voice to my teenaged self. I could go back to those years with the knowledge that I have now. Through Nishat, I could work through all of the messiness, the complication, and maybe help give that language I lacked to some teenagers who are struggling now.

Adiba Jaigirdar was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and has been living in Dublin, Ireland since the age of ten. She has a BA in English and History, and an MA in Postcolonial Studies. She is a contributor for Bookriot, and an ESL teacher. All of her writing is aided by tea, and a healthy dose of Janelle Monáe and Hayley Kiyoko. When not writing, she can be found ranting about the ills of colonialism, playing video games, and expanding her overflowing lipstick collection.

She can be found at adibajaigirdar.com or @adiba_j on Twitter and @dibs_j on Instagram.

Recent Comments