I grew up in the very beautiful Adelaide Hills in South Australia. It is a place of sweeping slopes of native bushland, pastoral valleys and vineyards; a place where kangaroos, koalas and other wildlife roam freely. It is Peramangk Country, bordering land belonging to the Kaurna and Ngarrindjeri Nations.

The colony of South Australia was always intended for free ‘settlers’ by British Parliament. Most of the nineteenth-century emigrants who ‘settled’ on this unceded Aboriginal Country were English. But many were also Prussians seeking religious freedom.

I have always been curious about the Prussians who ‘settled’ on Peramangk and Kaurna land. German influence on the Adelaide Hills region remains to this day in place names, foodways and viticulture. Hahndorf, with its cuckoo-clock shops and fachwerk buildings, and the Barossa wine region, home to Schutzenfests and a Liedertafel, continue to memorialise their Prussian ‘pioneers’ to the point of hagiography. My interest in them has always been personal: these persecuted Prussians are my ancestors. Were they as pious and hardworking as the common narrative would have it? To what extent were they complicit in the theft of Indigenous land and resources?

I began reading about historical journeys from Hamburg to ‘Port Misery’, the formation of towns such as Bethany and Hahndorf, Lobethal and Tanunda in the new Colony, and the lives of their Old Lutherans. After a time I found myself drawn – as I always seem to be – to that which was not easily found in the records, namely the lives and stories of women. ‘Maybe I’ll explore, in a creative sense, the value of friendship between these German women,’ I thought.

Then a few things happened. It was 2017. Australia voted in favour of same-sex marriage, and my girlfriend proposed to me. I realised that my original plan to write about the value of friendship between women, was not enough. I understood that my novel needed to be romantic, and that this story would entwine with the emigration of Prussian Old-Lutherans to the colony of South Australia. It would be a love story.

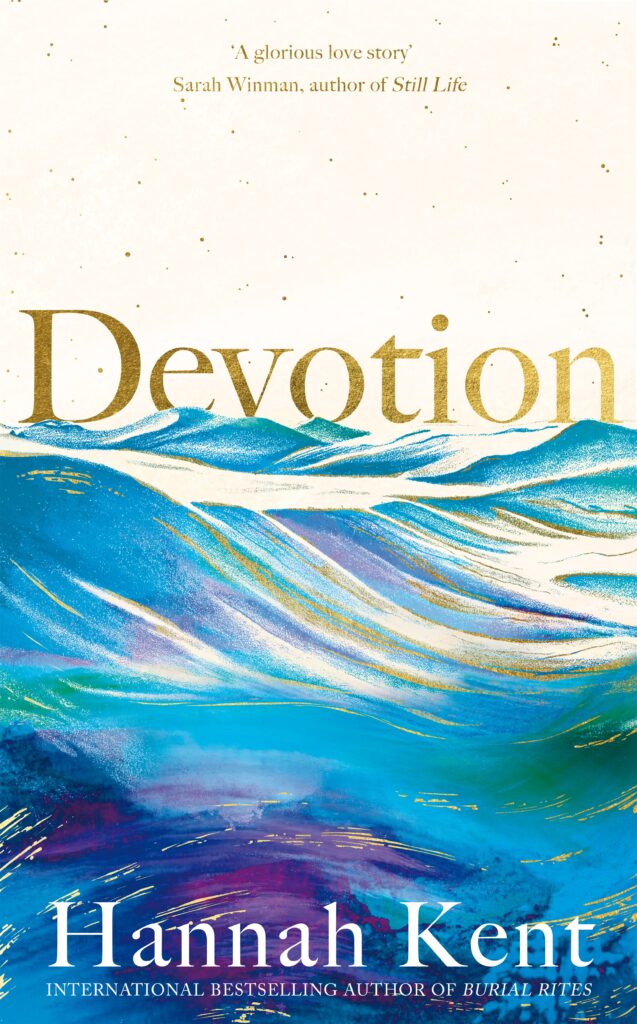

I am now married. My wife and I have since had two beautiful children, both born during the writing of this book. Devotion, in its articulation of music instead of silence, presence instead of absence, is very much a gift to my younger, queer, closeted self. I used to wonder if there were any stories like this out there, if such a thing might have happened.

Hannah Kent’s first novel, Burial Rites, has been translated into over thirty languages and was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, the Guardian First Book Award and the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. In Australia it won the ABIA Literary Fiction Book of the Year and the Indie Awards Debut Fiction Book of the Year, amongst others. Her second novel, The Good People, was also translated into many languages and shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize. Devotion is her third novel.

Recent Comments