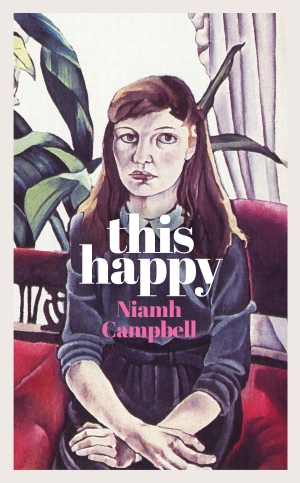

My book is coming out in the time of coronavirus. This doesn’t bother me as much as you might expect, but it does, perhaps, somewhat date its treatment of the Dublin political scene. This is not a central theme in This Happy but a mischievous context: my protagonist Alannah, a lazy socialist, is marrying a ‘baby Blueshirt’ left out in the rain and apparently not especially bothered by that. Mostly because they have incredible sex.

I have noticed the trope of bright but broke girls hobnobbing with the Establishment in Irish literature of late and I suspect it reflects pragmatism: how else is your Young Miss going to find out what really goes on? Certain English responses to the televised Normal People reveal a misunderstanding of Ireland that is also telling. The class system here is relatively porous – to a point.

This point is a limit Alannah meets. She doesn’t marry for money, but she is attracted to her husband’s boyish earnestness, his belief in his right to a career in politics simply because he belongs to the political class. Such confidence – along with the adenoidal accent that goes with it – is only gained by living a life in which connections dissolve obstacles. It is not even wickedness, just innocence.

Post-corona, we will see evidence of the damage innocence does when it is maintained by a rear-guard of aggression. There are people insulated by assets and large houses in lockdown right now, and there are people in direct provision, hotels, or just cramped house-shares for which they pay half of their income. If they still have income at all.

At a dinner party, Alannah clashes with a barrister who tells her there is no appetite for legalising abortion ‘at the grassroots’ of civic life – an argument which seems touchingly vintage now. She reminds him that she is the grassroots. We know history proves her to be on the right side of events that are, in the book, imminent; I wrote against a backdrop of cultural shifts that effected important but sometimes cosmetic changes to Irish life.

Real change must come at a deeper, material level, and a novel cannot do that. What it can do, however, is make a humane contribution to the world of literature, a space in which we reflect more than we fight. Polemic speaks to the ego, as it must, but art works on the heart.

Niamh Campbell was born in 1988 and grew up in Dublin. Her short fiction and essays have appeared in The Dublin Review, 3:AM, Banshee, Gorse, Five Dials, and Tangerine. She was awarded a Next Generation literary bursary from the Arts Council of Ireland, and annual literary bursaries in 2018 and 2019. She holds a PhD in English from King’s College London and is a current postdoctoral fellow for the Arts Council of Ireland at Maynooth University. She lives and works in Dublin.

Recent Comments