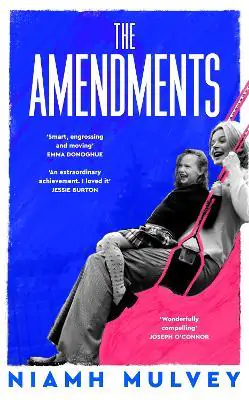

Niamh Mulvey shares a few words on she came about to write her new book, The Amendments.

Writing The Amendments was a strange and strangely joyful experience. The characters came to me in all their various dilemmas and madnesses and I had to let myself inhabit them in order to figure out what they wanted and needed – from me, from the world they were in.

To inhabit a character is a very bizarre thing to do – but reading fiction is itself really odd, when you think about it. When writing is not going well, you can kind of feel like an overgrown child playing with your dollies, hoping no one overhears. But when it does go well, it’s like a weird enchantment and the words surge forward and you find yourself in the midst of that miraculous thing – a new creation.

I’ve been a bit worried lately that the title of this book, The Amendments, is a bit ‘on the nose’ as they say, maybe obvious and gauche. But it really did demand to be called this. The amendments of the title refer to various constitutional amendments that happened or did not happen in Ireland between the nineteen-eighties and twenty-tens. And I see in that endless writing and re-writing a struggle to manage a tension between who we actually are, as a people, and who we would like to be (who that ‘we’ actually is, is another important and mainly unanswerable question).

It’s quite funny that this other referendum happened just now, just as the book is coming out, and so, like the diligent citizen I am, I poured over the wording, trying to figure out what I thought about the proposed changes. Referendums always initiate a highly politicized process, and, within all the verbal wrangling, there’s a useful reminder of how words and text can create a kind of reality – despite the gap that always, always exists between the world as it actually is and the world as we write it down. When you step back a little, there is a terrible kind of poignancy in that, in the limitations of language to ever fully capture experience and consciousness.

The amendments in my novel are in the background, the main characters are not particularly interested in them – but they feel them happening, they know they have implications for their lives, but they don’t really want to think about it. These characters want to hide from history, the loud, grand kind that happens in official texts. It’s in that gap – between the language (“the wording”), trying its best to hold together as many ideas as possible while still actually meaning something – and the experience itself, that’s where this novel sits.

You can now shop this on our website.

Recent Comments