For a long time, the Dubray bookshop in Grafton Street, Dublin kept a copy of The Book of Lost Things on its shelf of booksellers’ recommendations, along with a handwritten note from one of the staff. I always found it deeply flattering that a bookseller would take the time to enthuse in writing about one of my books, and was very sorry when the bookseller in question left to work in publishing, not least because The Book of Lost Things was then replaced by a different recommendation. These things hurt, you know.

I love notes left by staff in bookstores, and have bought so many books based on them. Dubray Grafton Street’s recommendations alone have led me to acquire Kings of the Wyld by Nicholas Eames, an amusing, imaginative 2017 fantasy novel that I doubt I would otherwise have chosen to read; Go With Me, a 2008 thriller by Castle Freeman, of which I had been completely unaware up to that point; and Child of All Nations, a 1938 novel by Irmgard Keun, told from the perspective of a nine-year-old girl named Kully, whose family has been rendered stateless by the Nazis in the build-up to the start of the Second World War. The latter has since become one of my favourite novels, and I’ve lost count of the number of copies I’ve given as gifts.

Some of us, I think, are a little embarrassed to ask a bookseller for a recommendation. It may, in part, be a wariness about then feeling obliged to buy something we’re not sure we want to read, just because we don’t want to hurt the bookseller’s feelings. I admit that this has happened to me on more than one occasion, and I now have a “politeness” shelf filled with books I’m never likely to get to. Occasionally I’ll give one of them a try, but only reluctantly, and with a success rate of about 50 per cent or less. It’s too late to bring them back now. Even if I tried, it would be my luck to find that the bookseller behind the register was the one who’d pressed the book on me to begin with, and I’m not sure I could bear the resulting look of disappointment on their face.

I’ve tended to do much better with those little notes, perhaps because they represent a cross-section of views and affections, and each bookseller has had to whittle a presumably long list of beloved books down to just one or two titles, before concentrating their opinion into a single paragraph. In addition, the note won’t hold it against me if, after glancing at the contents, I put the book back on the shelf. Neither, if I buy the book, will the note later ask me if I’ve read it, and if so, whether I enjoyed it. I will never have to lie to the note, or make it doubt its taste. Neither will the note ever judge me, and secretly find me wanting. The note is the reader’s friend, but also the bookseller’s.

And sometimes, if their book is fortunate enough to be chosen, the writer’s too.

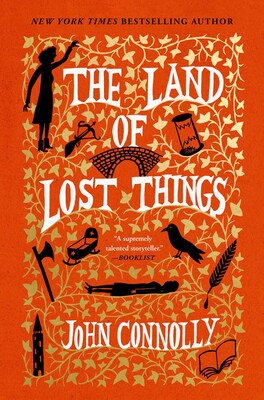

The Land of Lost Things, a sequel to The Book of Lost Things, is published by Hodder & Stoughton.

You can now pre-order The Land of Lost Things by John Connolly on our website.

Recent Comments