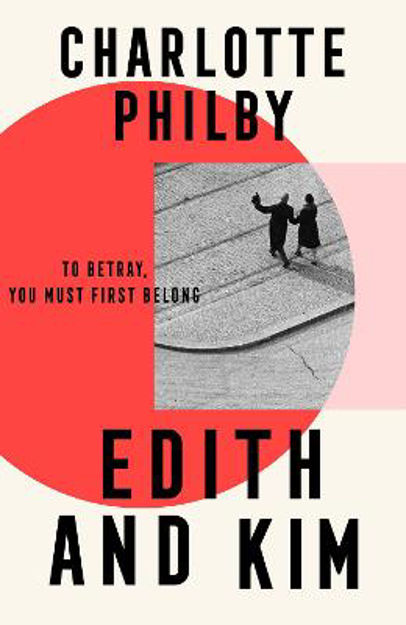

The irony is not lost on me that I was on the tube to the National Archives in London, of all places, the first time I read the name Edith Tudor-Hart.

Perhaps I had seen it before, or heard mention of Edith (nee Suschitzky) in passing over the decade or so that I had been reading intently around the life of my grandfather, the double agent Kim Philby. If I had, it had never stuck. That is hardly surprising given that she doesn’t exist in most of the official texts formalising the antics of the Cambridge Spies and their role in the Cold War, as I have variously found them. Despite having been one of the most pivotal figures in contemporary history, extraordinary efforts appear to have been made to write her out of it. One argument is that she was simply too good to be caught. Another is that the antics of ‘that foreign woman’– as she is termed in one of the countless SIS files that span from her first Communist rally in London in 1930, when she was eighteen, to her death in 1973 – were an embarrassment too many for the British establishment.

In 2010, my boyfriend and I travelled to Moscow. It was my first time there as an adult, following Kim’s footsteps to the city where he lived from 1963 after his exposure as the notorious Third Man, until his death in 1988. Our trip, which I charted for The Independent newspaper, where I worked at the time, was an effort to understand more about the life of my own father, John – Kim’s eldest son – who died of lung cancer the previous year. I was twenty-six and rather than have my questions answered by that trip, I found more opening up.

The more I learnt about my grandfather, the more these versions of his life seemed at odds with one another. In response, I spent years poring over what I could find about Kim Philby, beyond my own memories of him as a smiling old man in braces on family holidays to Russia when I was a child. Memories dominated by music and laughter, my father and Kim playing chess on the sofa, a bottle or six between them. I read everything I could get my hands on; poring over the endless letters he wrote to the family in London from behind the Iron Curtain. I interviewed journalists and friends – and those he betrayed – about their recollections of the man behind the mask; a man who had so many faces: friend, lover, father, traitor; each face as persuasive and contradictory as the last.

But it wasn’t until I was catching up on some reading on the tube to a talk at the National Archive, one winter’s evening many years later, that I consciously became aware of Edith Tudor-Hart, a woman referred to by fellow Cambridge spy, Anthony Blunt, in the newspaper article I was reading, as ‘The Grandmother of us all’. Since then, I’ve immersed myself in everything I can find about Edith, a woman whose commitment to her schizophrenic son was as unwavering as her commitment to the Soviet cause, which seized her whilst growing up in Vienna against the highly tense backdrop of the interwar-period and the rise of Fascism. It was here that she met a young Kim, who married Edith’s best friend Litzi, who was Jewish, in order to help her escape. And it was Edith who would introduce him to his future controller Arnold Deutsch a year later, in 1934, on a bench in Regent’s Park. A meeting that changed the course of history.

Kim famously said that he was two people, a political person and a private person and if forced to choose, the political would naturally come first. But I don’t believe Edith saw this as a choice. She didn’t have that luxury: she was both.

Thanks to a plethora of files held on Edith Tudor-Hart – who was followed, letters read and phones tapped for most of her adult life, and whose life was ultimately destroyed by Kim – I was able to piece together her movements. From Vienna to the Bauhaus, and then to London, Edith’s is an intoxicating story of a revolutionary, a lover, a single mother, and a spy. A woman who helped create Kim Philby as so many people know him, before being destroyed by him. This book is an effort to widen the lens to shine new light into the darker corners of a well-told story.

Given the serendipity of where and how I found Edith – silly as it may sound – it’s hard not to believe I didn’t choose to write this story, so much as, in a way, it chose me.

Charlotte Philby worked for the Independent for eight years, as a columnist, editor and reporter, and was shortlisted for the Cudlipp Prize at the 2013 Press Awards for her investigative journalism. Founder of the online platform Motherland.net, she regularly contributes to the Guardian and iNews, as well as the BBC World Service, Channel 4 and Woman’s Hour. She has three children and lives in London. Charlotte is the granddaughter of Kim Philby, Britain’s most famous communist double-agent.