Diary of a Young Naturalist follows seismic changes in your life, as the seasons turn. What do the seasons, and their transitions, symbolise to you? Do they reveal something about humankind and nature?

We are all part of a constant cycle, an interconnecting eco system – the web of life. Seasonal transitions are not separate from us. Subconsciously and consciously they are a massive part of all our lives. How often do we talk of the weather and how joyous do we all feel when spring comes?

My intense connection to the world means that perhaps I feel these shifts more deeply than others do. I notice the way the air changes, the smells that subtly change with each season. I revel in the first blackbird and thrush song, when the celandine and primroses bloom. The turning of leaves in autumn. The whooper swans arriving from Iceland. Each small unfurling is a message that all is well in that moment. Everything else may be in chaos, but these recurrent forces of nature still exist. To me, that is very comforting.

The seasons connect us to the land – it is a subliminal ancestral echo. It connects us to our communities, and it balances our brains. There is a deep-seated need to be in sync with the natural world, whether we are aware of it or not. Those who work the land and are strongly connected to it have an acute awareness of this.

You speak beautifully of how ‘watching daphnia, beetles, pond skaters and dragonfly nymphs is a medicine for this overactive brain’. How do you use nature as a source of comfort? How would you recommend others to explore the natural world as a source of self-remedy, and escape?

Exploring the natural world is second nature to me. My interest and curiosity were already present before I realised the calming effect it had on my mind. During particularly tough times, when I was bullied quite heavily, nature was my obvious escape. Alongside the safety net of my home and family, the outside world distracted me from dwelling on the negative thoughts, inner feelings and intense bullying I was encountering. I used the power of noticing – of observing the intricacies of the living world, and all the species that inhabit my local area – to provide the sustenance that my wearied spirit required.

So, I don’t really use nature as a source of comfort per se; instead, I discovered it through an already present love and fascination for our world. That is the only recommendation I have: to notice, love and care for our beautiful planet.

We can take a walk in two ways. We can walk to enjoy the exercise (this is great and necessary for our health), or we can walk intentionally and notice all we see, smell, touch and explore. Take photos of plants, insects, birds. Learn more about them. When we notice things and ask ourselves questions, we broaden our knowledge. It seems trite to state something so innate to humankind, but unfortunately, we are fast losing our connection to nature. Life has become so fast-paced, people are rushing everywhere; there doesn’t seem to be much time to truly appreciate our only home. This place provides us with clean air, water and an ecosystem so magnificent that we all depend on it for survival.

During lockdown, people have rediscovered the art of slowing down and noticing their surroundings. I hope this continues and deepens, and leads to a heightened love and respect for our glorious earth.

One admiring reviewer praised your blend of ‘poetry, punk and puffins’ in your writing style. From poetry to philosophy to music, Seamus Heaney to The Clash, how does this patchwork of art forms influence your writing? Does each serve a different purpose to you?

I feel that art doesn’t serve. Art is expansive, revealing. It layers our lives with meaning and weaves its magic in many ways, enlivening our emotions. I have a very curious mind and I constantly seek out things that spark my interest. My parents have had a significant impact on my tastes though. When I was growing up, punk music was played constantly in the car. We didn’t have holidays, expensive clothes, technology…but we had our books and inexpensive art prints. This childhood has expanded and enriched my world in ways that naturally pour out onto the page. These influences inhabit my being and just come out instinctively.

I do listen to music as I write. Punk music is very focusing for me and Irish folk music allows me to drift. It crackles my imagination. I can differentiate the lines in my book by the music I was listening to when I wrote them!

It seems overtly fan-boyish to say, but I think of Seamus Heaney almost every day. When I observe nature, the lines of certain poems flush through me. Heaney has definitely influenced the rhythm I write to, the beat of every word.

Family sits at the heart of your book. In your words, the McAnultys are ‘as close as otters’. How do your parents and siblings inspire you – in your writing, values or wider pursuits?

My family inspire me every day. Many people have commented, based on what I wrote in my book, that my family are somewhat detached from normal society. But I feel we are rooted in what in is good and beautiful about our world. I didn’t chronicle our family life in minute detail, but we have a wonderful community that we are involved in and deeply connected to. But I do get how we may be perceived as different.

Loving nature is instinctive within our family. Our innate curiosity was never discouraged. Every interest of mine was nourished by visits to the library, free museum trips and many hours spent outside – though I now know this was difficult for them. My parents have always encouraged our individuality and celebrated our differences and abilities, without money or material things, just words and unconditional love. I have learnt great empathy from them. My parents have eclectic music tastes; they love punk, indie and Irish folk music. They saw Nirvana live and they have wonderful stories about their youth that really inject joy into our family life.

My siblings are such brilliant human beings and although we have many arguments (typical siblings!) we are definitely as ‘close as otters’. My brother and I still share a room and talk long into the night – which definitely creates sparks for my writing. My sister is still obsessed with insects, although less so with fairies these days. Her humour lightens my sometimes-morose teenager ways and some of her one-liners definitely end up in my notebooks! We are all connected in our little familial ecosystem and we depend on each other. I hope this will always be the case.

In your diary we follow you to an Extinction Rebellion protest. Your prose is laced with an urgency to save our earth. How do you hope your reader will change after finishing your book? What action must they take?

I have received a huge response from readers to my book, and although they have reacted in varied ways, there is one constant message I receive: they look at the world a little differently now.

Some say they have formed a deeper connection to nature since, as they have noticed more the interconnectedness of every living thing. I had no prior expectations of how readers would respond to this book, and this I could never have predicted.

I hope that new readers will change in ways that feels meaningful to them. That is all I can ask for, and any small change people make because of my words is momentous for me. However, though individual action is fantastic, what we really need is systemic change. We really need to vote for politicians who will put the natural world at the centre of their decision-making, because that benefits all of us.

I’m not sure that politics is ready for that right now, but we can push harder for politicians to consider the imbalance between economic growth and the destruction of the natural world. I have never been one to demand what people should do, or how they should act – but thinking consciously about how each of our own decisions affects the planet is a really good thing for everyone. If I could impart three ideas, it would be: notice more; buy less; and waste nothing. Living by these three simple principles is the root of my family’s life. We’ve never had much money and so we have appreciated everything and wasted nothing.

You started writing Diary of a Young Naturalist as a young teenager, and a lot has changed since then. Is there a new idea or project occupying you – is a new book emerging on the horizon?

I am very excited that my first book for younger readers, Wild Child, is coming out in July this year. It’s a multi-sensory journey though nature and includes poetic prose, lots of fun accessible science, and activities and advice for young people on how they can deepen their connection to nature.

Next year will see the release of Wanderings of a Young Naturalist, my next work of narrative non-fiction. In it I will travel around Ireland to explore our changing relationships to the land. It won’t be in diary form like this book, but it is a natural continuation of my fascination and desire to understand the world by looking back at ancient sites, archaeology and the momentous changes to our natural landscapes. I am so humbled to have these opportunities, to write about urgent and prescient quandaries, to question myself, explore and learn. I know it is not the normal trajectory for a teenager, but writing is now like breathing. I can’t stop. At least for now.

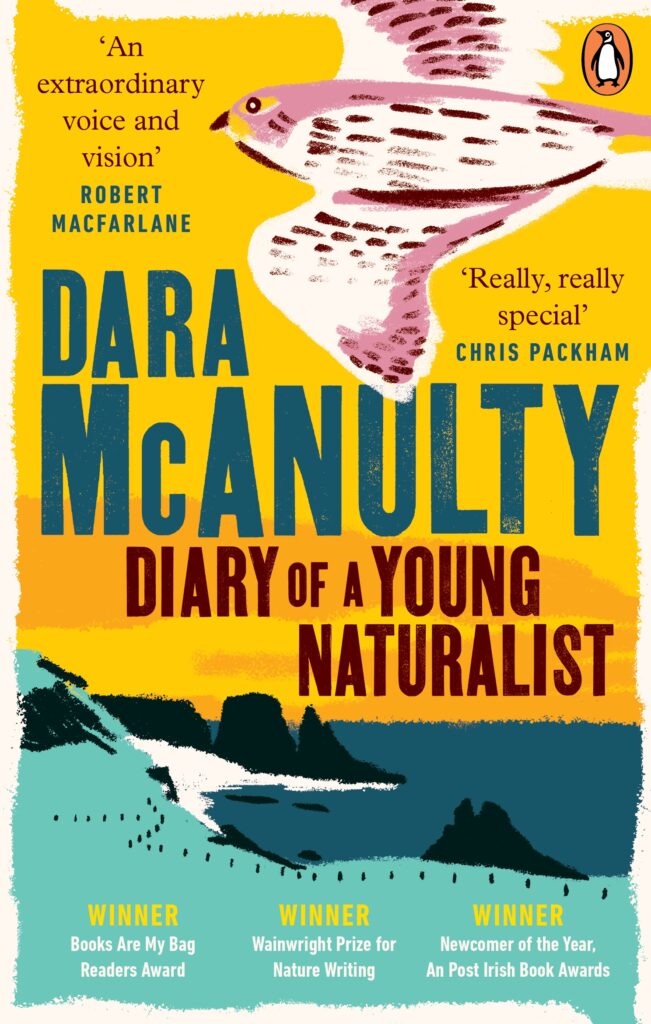

Dara McAnulty is a 17-year-old autistic naturalist, conservationist and activist from Northern Ireland. After writing his online blog ‘Naturalist Dara’ for over three years, and articles for many UK Wildlife NGOs, Dara published his debut book, Diary of a Young Naturalist, in 2020. He won the Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing in 2020, becoming the youngest ever winner of a major literary prize – alongside many other awards. Dara is a passionate and fervent campaigner for the natural world and a dedicated fundraiser, volunteer and wildlife recorder. He is the youngest ever winner of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds Medal for services to conservation and nature. He is also the recipient of 10 Downing Street’s ‘Points of Light’ and the winner of The Daily Mirror Young Animal Hero award. He lives with his family and Rosie the rescue-greyhound at the foot of the Mourne Mountains in County Down.

Recent Comments