Some people remember where they were when they heard that Kennedy had been shot. I remember where I was when I first read the piece about Mod that opens It Gets Me Home, This Curving Track. Sitting in a kitchen in rural New Jersey over Sunday morning coffee and bagels, cradled for half an hour in Ian Penman’s words. The arrival of this book is like the arrival of a new album from Scott Walker or Robert Wyatt: a long-vanished figure emerges from the shadows to hand you a gift, then disappears for another decade. The difference is that the late work of the late Scott Walker was relentlessly hard going, definitively stating that the sun wasn’t going to shine any more. These essays are as lucid and intoxicating as a good martini.

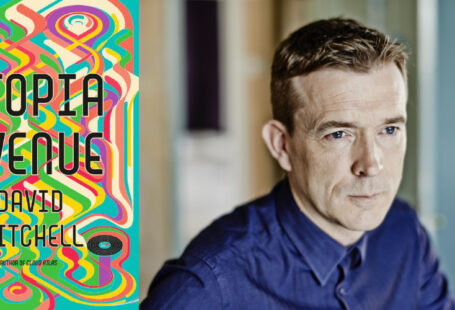

Most of them appeared at yearly intervals in the London Review of Books, others in the City Journal. They started life as book reviews, in the loose, expansive sense characteristic of the LRB, where the book under review is only the pretext for an extended meditation on its subject. Penman writes about Frank Sinatra and James Brown, Elvis and Prince. You don’t need to be a fan — I haven’t listened to Sinatra since one of my flatmates walked off with my copy of Come Fly With Me twenty years ago. (Come to think of it, the same flatmate walked off with my copy of Sex Machine…I see a pattern emerging). The genius of these essays is in the way they demonstrate that what you thought you knew about these musicians, these pop cultural monsters, was only a sketch, a caricature, a cheap disguise.

Penman is an extraordinarily perceptive listener, always alert for the human moment captured in recordings. It’s as though he’s come to inhabit them, to wear them like a second skin. But more than that, he’s a consummate performer, capable of evoking those moments in writing that combines incisive criticism with a soloist’s flourish. He can start an essay on Prince with no fewer than three epigraphs, quoting Walter Benjamin, Fernando Pessoa, and Gertrude Stein, and still make it work.

You could track these essays down in the journals that originally published them, skim-read them online while snatching another workday lunch maybe. But they read a little differently collected between the matte white covers of a Fitzcarraldo paperback. They’re worth taking time over, savouring the distilled years of listening that have gone into them. Maybe the royalty will fund another of his #CharityShop finds, maybe even a worthy #FirstDrinkSoundtrack. Do we owe him a living? ’Course we do.

Recent Comments