That’s just what translation is, I think. That’s all speaking is. Listening to the other and trying to see past your own biases to glimpse what they’re trying to say. Showing yourself to the world, and hoping someone else understands.

If you somehow missed Rebecca F. Kuang’s debut Poppy War trilogy, which followed the escapades of Rin, the most morally grey protagonist ever put to paper, then I’d advise you to stop reading this blog post and go get a copy from your local bookshop. A military-fantasy series inspired by 20th century Chinese history and shamanism, The Poppy War has all the brutality of A Song of Ice and Fire and all the fun of Avatar: The Last Airbender. Finishing the trilogy left me destitute and broken. So naturally when I heard about Babel, Kuang’s latest foray into fantasy, I had to get my hands on it. I am a glutton for a broken heart, apparently.

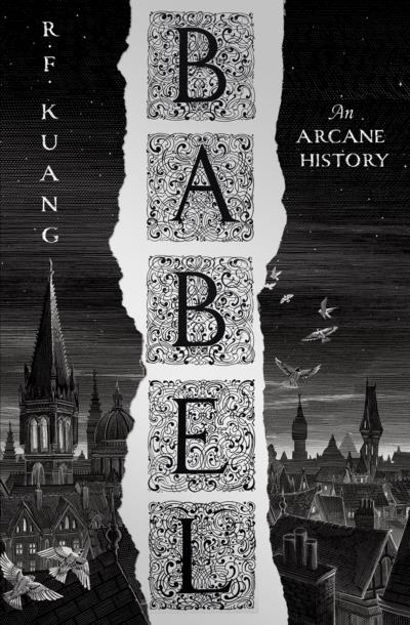

Babel (fully titled: Babel, or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution) is a dark academia novel which takes place in an alternate 19th century Oxford. Orphan Robin Swift is taken from his home in Canton to England by the mysterious Professor Lovell and is rigorously trained in Classics and Chinese to prepare for his eventual enrolment in Oxford’s Royal Institute of Translation, also known as Babel. However, Babel is not only the centre of translation, but of magic. It is where silver working happens, a process which catches the meaning between words lost in translation in silver bars. These silver bars can be used for anything, from exploding like grenades to providing power to entire cities.

Finally at the school of his dreams, with a close cohort of friends, Robin is told he should feel grateful for what he has been given. But when it becomes clear that he and his friends will never be fully accepted by their wealthy and white peers, the cracks in the university become harder to ignore. Robin finds himself stuck between two separate ideologies. The professors at Babel are adamant that the silver work they do bridges countries together and imposes peace between people, while the secret Hermes Society say the silver Babel makes is used to help the imperial expansion of Britain. Robin must soon decide what side of the empire he wants to be on.

Academia in general has a history of classism, racism and sexism, something that the dark academia genre does not typically challenge or even address. Recently, the overwhelming whiteness in academic spaces has been played with in novels like Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé’s Ace of Spades. Kuang follows this thread in Babel, using her own experience as a Chinese American student at Oxford to highlight the colonial history behind typically prestigious British universities. Even the magic system in Babel is tied to silver making and the act of translation, showing how language can be used as a weapon of imperialism.

Babel is clearly written from a place of love for both language and academia. It engages with and criticises the history of imperialism behind institutions like Oxford, but it is also an ode to the relationships that blossom in academic spaces, the long nights spent with friends, the endless cups of tea while cramming for exams, the shared experiences that bring us closer to one another. Moments we don’t realise are special until they have already passed.

This is one of my favourite books I have ever read, and it is also the first-time footnotes have made me cry. Fun!

If you’re a fan of fantasy, dark academia, history, etymology, or just good books in general, I urge you to read Babel.

Recent Comments